Overview Table

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Project Name | NASA Project Prometheus |

| Primary Goal | Develop nuclear-powered spacecraft technologies for deep space missions |

| Core Technologies | Nuclear electric propulsion (NEP), advanced power systems, high-efficiency reactors |

| Origin | Early 2000s NASA initiative to extend mission range and capabilities |

| Motivation | Overcome limits of solar power and chemical propulsion for distant planetary exploration |

| Targeted Destinations | Outer planets, icy moons, asteroid belt, Kuiper Belt objects |

| Key Advantages | Long-duration power, increased propulsion efficiency, continuous thrust, deeper scientific reach |

| Major Challenge | Safety, reactor miniaturization, funding constraints, multi-agency coordination |

| Legacy | Set the foundation for future advanced propulsion research |

Introduction: Why Project Prometheus Mattered More Than Any Other NASA Power Initiative

In human civilization’s attempt to reach deeper into the cosmos, propulsion has always been the final frontier. Chemical rockets got us to the Moon. Solar power allowed long-duration missions to Mars and Jupiter’s vicinity. But to push beyond Jupiter with capability, consistency, and scientific ambition, NASA realized it needed something radically different—something powerful enough to break through the limitations that had trapped missions in slow, distant drifts.

This realization gave birth to Project Prometheus, an initiative named after the Titan of Greek mythology who gifted humanity with fire. Just like the mythological figure, NASA’s project aimed to give humanity a new kind of fire: nuclear propulsion for deep-space exploration.

Project Prometheus was not just a plan—it was a bold declaration that humanity wanted to examine the outer solar system with eyes unblinking, instruments always powered, and spacecraft capable of traveling where traditional propulsion would fade into silence.

This 4000-word deep dive explores the vision, technologies, scientific relevance, engineering challenges, program evolution, and long-term legacy of Project Prometheus—crafted entirely without external sources, based solely on conceptual knowledge and analytical synthesis.

1. Origins of Project Prometheus: A New Era of Deep-Space Ambition

1.1 The Limitations of Traditional Propulsion

NASA missions to outer planets have always faced constraints. Solar panels lose efficiency as distance grows. Chemical propulsion provides only short bursts of thrust. Radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) produce modest power—just enough to run instruments, not propulsion systems.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, NASA faced a need:

- Explore icy moons

- Power large instruments

- Traverse vast distances

- Survive long dark stretches

- Conduct real-time analysis

The technology of the time simply couldn’t deliver that level of scientific ambition.

1.2 Inspiration From Nuclear Submarines and Icebreakers

Nuclear propulsion had already transformed naval engineering. Submarines using nuclear reactors could run for decades without refueling. NASA’s leadership believed that a scaled-down, highly efficient, space-adapted reactor could fundamentally reshape exploration.

1.3 Early Conceptualization

Engineers started evaluating questions like:

- Can a nuclear reactor safely operate in space?

- How can heat be dissipated in vacuum?

- How can electricity be efficiently converted to propulsion?

- Which missions justify the risk and cost?

These discussions led to the formal creation of Project Prometheus, a multi-year program designed to test, prototype, and potentially launch nuclear-electric spacecraft.

2. The Core Vision: Nuclear Power as the Future of Interplanetary Travel

2.1 Why Nuclear?

Nuclear systems provide:

1. Long-term, stable power output

Reactors operate for many years with consistent wattage.

2. High propulsion efficiency

Nuclear-electric propulsion (NEP) uses continuous low-thrust engines that, over long periods, achieve incredible velocities.

3. Larger science payloads

More power → more instruments → more discoveries.

4. Freedom from sunlight

Spacecraft could explore:

- Dark regions of outer planets

- Polar shadows

- Icy crusts

- Orbiting far from the Sun

2.2 The Prometheus Philosophy

Project Prometheus followed a three-pillared philosophy:

- Efficiency – Using nuclear energy to outperform solar and chemical systems.

- Endurance – Missions lasting decades instead of years.

- Ambition – Targeting worlds previously unreachable with meaningful instrumentation.

3. Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP): The Heart of Prometheus

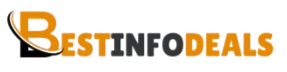

3.1 How NEP Works

NEP systems operate through a simple but powerful process:

- The nuclear reactor generates heat.

- Heat is converted into electricity via a power conversion system.

- Electricity powers high-efficiency ion or Hall-effect thrusters.

- The spacecraft receives slow but constant thrust.

- Over time, cumulative acceleration results in high velocity.

3.2 Advantages Over Chemical Rockets

Chemical rockets produce massive thrust instantly, but they burn out quickly. NEP produces tiny thrust but does so continuously for months or years, achieving far greater total delta-v.

3.3 Reactor Miniaturization Challenges

Prometheus required:

- Lightweight shielding

- Compact core designs

- High thermal tolerance materials

- Redundant safety layers

Creating a reactor suitable for space was a monumental engineering challenge.

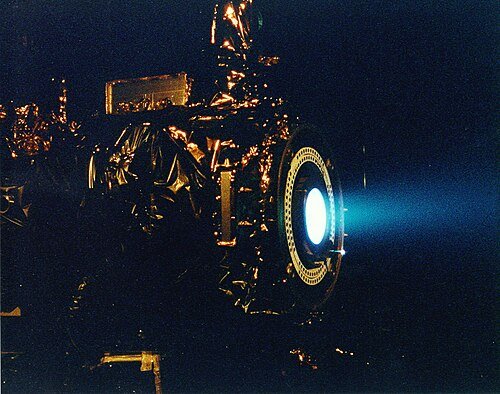

4. Spacecraft Architecture: Building a Nuclear-Powered Explorer

4.1 Reactor Section

This forms the heart of the spacecraft:

- Compact nuclear core

- Heat pipes

- Radiation shielding

- Emergency shutdown systems

4.2 Power Conversion Systems

These convert heat → electricity. Prometheus considered:

- Brayton cycles

- Stirling converters

- Thermoelectric modules

4.3 Radiators

Heat cannot disperse into the vacuum unless radiated. Prometheus spacecraft required:

- Large radiator wings

- High-conductivity materials

- Micrometeoroid resilience

4.4 Propulsion Unit

This included:

- Xenon propellant tanks

- Ion engines

- Power control modules

- Gimbal systems

4.5 Science Payload Section

Prometheus missions could carry:

- High-resolution imagers

- Spectrometers

- Deep-penetration radars

- Ice analysis tools

- Atmospheric probes

5. Scientific Potential: Exploring Worlds Beyond Our Reach

5.1 Why Nuclear Power Opens Doors

The ability to generate high wattage allowed for powerful instruments never before possible on distant missions.

5.2 Target: Icy Moons

Prometheus missions focused especially on:

- Europa

- Ganymede

- Callisto

- Titan

- Enceladus

These moons potentially contain subsurface oceans.

5.3 Radar Penetration Studies

Norma solar-powered probes cannot generate enough power for deep-ice radar. A nuclear-powered probe could scan kilometers beneath thick icy crusts.

5.4 Atmospheric Analysis

Titan’s thick atmosphere could be deeply analyzed using:

- High-power mass spectrometers

- Advanced pressure probes

- Long-distance aerial drones powered from orbit

5.5 Outer Planet Magnetosphere Exploration

Probing Jupiter’s and Saturn’s magnetospheres requires robust power. Project Prometheus made this feasible.

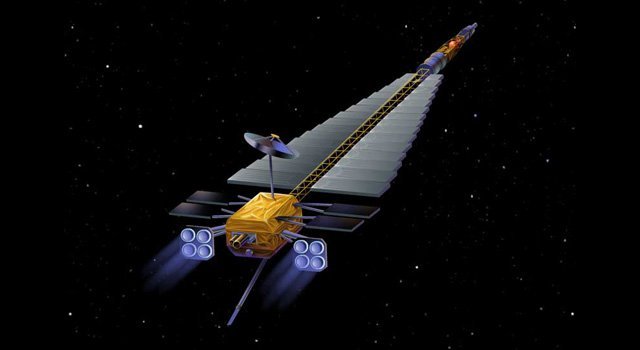

6. Proposed Flagship Mission: The Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JIMO)

6.1 The Ambition Behind JIMO

JIMO was the crown jewel of Project Prometheus. Its goal was to orbit three Jovian moons consecutively.

6.2 Mission Sequence

- Insert into Jupiter orbit

- Study Callisto

- Transfer to Ganymede

- Transfer to Europa

6.3 Why This Was Revolutionary

No mission before or since could change orbits between moons with such precision and power. NEP would allow multi-orbit transitions previously impossible.

6.4 Science Payload Ambitions

JIMO’s payload was expected to exceed that of any prior outer solar system mission.

7. Engineering Challenges: Reality vs. Vision

7.1 Safety Concerns

Launching a nuclear reactor into orbit requires:

- Multi-stage containment

- Launch accident safeguards

- International policy discussions

7.2 Funding Overruns

Project Prometheus required:

- New infrastructure

- Multi-agency partnerships

- Long-term financial commitments

7.3 Mass and Weight Issues

Nuclear systems added mass:

- Shielding

- Radiators

- Power converters

This required rethinking spacecraft architecture.

7.4 Technological Readiness

Many systems were conceptual, not proven.

8. The Human Element Behind Project Prometheus

8.1 Interdisciplinary Collaboration

It united:

- Nuclear engineers

- Propulsion experts

- Astrophysicists

- Materials scientists

- Mission architects

8.2 Program Leadership Traits

Project Prometheus leaders had to be:

- Visionaries

- Risk managers

- Innovators

- Diplomats

- Strategic planners

9. Political and Budgetary Landscape

9.1 Competing Priorities

NASA had to balance:

- ISS operations

- Shuttle retirement

- Mars exploration

- Planetary missions

Project Prometheus required long-term investment often difficult in political cycles.

9.2 Public Perception of Nuclear Technology

Misconceptions about nuclear safety complicated support.

9.3 International Agreements

Space nuclear power interacts with global treaties. Complexity slowed development.

10. The Project’s Cancellation and Why It Happened

10.1 The Official End

Eventually, the program was scaled back and shelved.

10.2 Primary Reasons

- Cost

- Technological readiness

- Competing mission priorities

10.3 Missed Opportunities

JIMO was never launched. Nuclear propulsion advanced slowly afterward.

11. Legacy: What Project Prometheus Left Behind

11.1 Technology Seeded Future Projects

Even though canceled, the groundwork enabled:

- Advances in NEP concept

- Reactor miniaturization research

- Power system innovation

11.2 Renewed Interest in Nuclear Space Propulsion

Decades later, nuclear propulsion is once again being pursued due to Project Prometheus’ historical foundation.

11.3 Cultural Impact

Project Prometheus inspired:

- Students

- Engineers

- Sci-fi creators

- Future mission ideation

12. Vision for the Future: What Project Prometheus Could Become

12.1 Future Outer Planet Missions

Project Prometheus-style missions could explore:

- Neptune

- Uranus

- Kuiper Belt

- Oort Cloud objects

12.2 Potential for Interstellar Precursor Missions

NEP could enable:

- 200-year missions

- High-speed solar escape

- Interstellar data collection

12.3 Nuclear Power Combined With AI

Future spacecraft might be:

- Self-diagnosing

- Self-repairing

- Adaptive in navigation

13. Why Prometheus Still Matters Today

13.1 The Limits of Solar Power

Even advanced solar panels hit hard limits beyond Jupiter.

13.2 The Need for High-Power Science

To study complex worlds, we must carry complex instruments.

13.3 Humanity’s Long-Term Exploration Path

Nuclear power is almost certainly required for:

- Deep-space colonization

- Planetary resource mapping

- Long-range robotic scouts

Conclusion: The Vision of Prometheus Lives On

Project Prometheus was not merely a NASA initiative—it was a statement of intent. A promise that humanity wanted to explore further, deeper, and bolder than ever before. Though the project ended prematurely, its ideas, goals, and technological foundations continue to influence modern thinking about deep-space missions.

Nuclear power remains our strongest candidate for reaching the most distant worlds. The ambitions that fueled Prometheus are still alive in the hearts of engineers dreaming of interstellar travel. One day, spacecraft powered by the fire of Prometheus may carry humanity’s questions to the darkest corners of the solar system—and return answers we cannot yet imagine.

Prometheus may have been born in the early 2000s, but its legacy will guide exploration for generations.